During an interlude in John's Apocalypse, we hear a roll call of one great crowd (144,000 from the tribes of Israel), but then we see another, even bigger crowd:

After this I looked, and there was a great crowd that no one could number. They were from every nation, tribe, people, and language. They were standing before the throne and before the Lamb. They wore white robes and held palm branches in their hands. (Revelation 7:9 CEB)

This innumerable crowd proceeds to shout out a chorus of praise, and the angels echo back with one of their own. This is apparently a heavenly worship scene, in the throne room of God, complete with the twenty four elders and the four living creatures, fixtures in the book of Revelation from chapters 4 and 5.

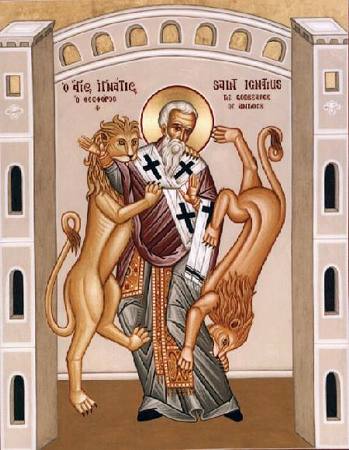

The size and transnational nature of the crowd is not to be underestimated. It apparently consists of martyrs who died in a great persecution/hardship/tribulation. θλῖψις (thlipsis) is the word in Greek, and it connotes great pressure and affliction.

Then he said to me, “These people have come out of great hardship (θλῖψις). They have washed their robes and made them white in the Lamb’s blood. This is the reason they are before God’s throne. They worship him day and night in his temple, and the one seated on the throne will shelter them. They won’t hunger or thirst anymore. No sun or scorching heat will beat down on them, because the Lamb who is in the midst of the throne will shepherd them. He will lead them to the springs of life-giving water, and God will wipe away every tear from their eyes.” (Revelation 7:14b–17 CEB)

This passage is probably most naturally read as a scene of heavenly reward - the faithful have come out of the θλῖψις and are now resting in God's shelter, where they don't have to worry about food or water or sunburns or tears. The Lamb shepherds them and leads them to life-giving waters - it's Psalm 23, fulfilled!

The implication seems to be that they were faithful through the θλῖψις and that their association with the Lamb in life has brought them - through the Lamb's blood and their own death - to this shepherding relationship with the Lamb post mortem. The note is pastoral: stay faithful in spite of the θλῖψις, because due to the Lamb, things will not always be this way.

But another angle sticks out to me here. These people are before God's throne because of their white robes that have been washed in the Lamb's blood. That sounds like baptism - the white robe, the theme of washing, the association with Christ and specifically his death - that's baptism.

They worship; God shelters; they don't hunger or thirst. This sounds like a prototypical early Christian community, gathering for worship (understanding that to be under the protection and provision of God), and the one with much sharing with the one who has little.

In this heavenly vision the sun's scorching rays aren't a danger to these martyrs, but not because the sun ceases to be necessary as in Revelation 21, but specifically because of the Lamb's shepherding. Christ is guiding and protecting them as a shepherd would do. Another word for shepherd is "pastor."

And of course in this vision they are flushed with life-giving water, and God is wiping away their tears.

But aren't we, in the church today, supposed to wipe away each other's tears? The Samaritan woman in John 4 receives life-giving water, which then bubbles up into eternal life for her, but it also bubbles over to quench her life-thirsty neighbors as well. In addition to the obvious baptism image, couldn't we also read this as something we in the discipleship community do for each other and for the world?

Christ shepherds them - he pastors them - but the church today also has pastors, who hopefully share in their own way in the spirit of Christ's pastoring, through leading the people to these life-giving waters.

The scorching sun must be connected to the curse of labor in Genesis 3, and it's easing is at least a heavenly expansion of the Sabbath easing of that curse. But might the curse of labor also be eased in the context of a community constantly looking out for each other, carrying each other's burdens? The same point goes for food and drink with their lack of hunger and thirst - the sharing of goods in Acts 2 and 1 Corinthians 11:17ff. Indeed, isn't this whole paragraph a kind of apocalyptic re-imagining of Acts 2:42-47?:

The believers devoted themselves to the apostles’ teaching, to the community, to their shared meals, and to their prayers. A sense of awe came over everyone. God performed many wonders and signs through the apostles. All the believers were united and shared everything. They would sell pieces of property and possessions and distribute the proceeds to everyone who needed them. Every day, they met together in the temple and ate in their homes. They shared food with gladness and simplicity. They praised God and demonstrated God’s goodness to everyone. The Lord added daily to the community those who were being saved. (Acts 2:42–47 CEB)

To bear each other's burdens is at some level to bear each other's θλῖψις - to come into the community of Jesus followers should mean being washed in Jesus' blood through baptism, but it also should mean to come out of θλῖψις. Suffering and hardship are still realities for us, but they should be made lighter and less substantial.

Death is surely transformed in this passage - this vision of the dead is no hellish ending or annihilation. But this must also be taken to be a picture of the church as well. In baptism we die and rise with Christ, passing through his θλῖψις on the cross and in some sense departing from our own. This is at least partially substantiated materially by what the theologian James Wm. McClendon describes in terms of the church as a community of care engaged in the practice of "watch-care."

And so in this passage I think we see not just a picture of martyrs on the other side of the grave, comforted and pastored in a post-θλῖψις existence. We also see a picture of the community of faith now, still somehow in the midst of θλῖψις and under intense pressure from all sides, but abiding together as they abide in the Lamb - after all, the word "martyr" in Greek just means "witness."

This end-picture, this image of transformation, is not just for the end but, under the gracious pastoring of the Lamb and the martyrdom/witness of God's people here and now, might just as well become a now-picture. May it be so.

A few weeks ago I went to a forum for everyone who holds a formal leadership position (mostly members of the myriad of committees) in the Texas Annual Conference of the United Methodist Church. The conversations were mostly interesting and fruitful, but I did notice one recurring theme that I found disappointing: most of the discussions of what it meant to be missional - a popular buzzword at this and other recent conference gatherings - were aimed primarily at how to get more people to come to our churches. The watch-word of the day was, "Why?"; indeed, that's the watch-word for the next four years in our conference. But the big "Why?" question that remains unexplored is why are the most interesting things we can think about to make our churches more 'missional' basically directed towards getting more 'butts in the pews'? We would be much more interesting and much more faithful if we concerned ourselves a little more with how we send our members out into the world than how we get more members in. And then, when we do actually get new members in the body, we can actually invite them to join us in doing something other than just expanding membership.

Then last week I went to our conference United Methodist Women's fall festival, where I was invited to lead a 'focus group' about how that storied ministry could better reach out to youth and other young people. But most of the ideas that came up and generated excitement had to do with sometimes creative ways of getting youth and young people to one way or another come to their 'circles' or their churches. The thought was that if we could just get more young people to come to us, then we might be able to figure out what to do with and for them. Ideas included inviting local teens who like basketball to come play basketball on the church grounds, or to come to a free community meal and stick around for Bible study. I pointed out that these attempts at outreach were really more like 'in-reach', and challenged them to think about ways they could go out and meet youth on their home turf. Someone commented that youth who come to in-reaches like those listed above probably feel really awkward, and we made the connection that in legitimate outreach it would be the church who would have to surrender home field advantage and meet youth where they already are, and thus bear the bulk of the discomfort.

A few weeks ago I went to a forum for everyone who holds a formal leadership position (mostly members of the myriad of committees) in the Texas Annual Conference of the United Methodist Church. The conversations were mostly interesting and fruitful, but I did notice one recurring theme that I found disappointing: most of the discussions of what it meant to be missional - a popular buzzword at this and other recent conference gatherings - were aimed primarily at how to get more people to come to our churches. The watch-word of the day was, "Why?"; indeed, that's the watch-word for the next four years in our conference. But the big "Why?" question that remains unexplored is why are the most interesting things we can think about to make our churches more 'missional' basically directed towards getting more 'butts in the pews'? We would be much more interesting and much more faithful if we concerned ourselves a little more with how we send our members out into the world than how we get more members in. And then, when we do actually get new members in the body, we can actually invite them to join us in doing something other than just expanding membership.

Then last week I went to our conference United Methodist Women's fall festival, where I was invited to lead a 'focus group' about how that storied ministry could better reach out to youth and other young people. But most of the ideas that came up and generated excitement had to do with sometimes creative ways of getting youth and young people to one way or another come to their 'circles' or their churches. The thought was that if we could just get more young people to come to us, then we might be able to figure out what to do with and for them. Ideas included inviting local teens who like basketball to come play basketball on the church grounds, or to come to a free community meal and stick around for Bible study. I pointed out that these attempts at outreach were really more like 'in-reach', and challenged them to think about ways they could go out and meet youth on their home turf. Someone commented that youth who come to in-reaches like those listed above probably feel really awkward, and we made the connection that in legitimate outreach it would be the church who would have to surrender home field advantage and meet youth where they already are, and thus bear the bulk of the discomfort.