Before you eat, you really should wash your hands. The world is full of germs and dirt and grime and other gross stuff. You touch a lot of things during the course of a day, and you don't know where that stuff has been!

Those are the kinds of things moms usually tell kids anyways. But they probably have a point. Moms are smart sometimes.

In Mark, the beginning of the gospel doesn't have a genealogy or a birth story or magi or shepherds. That's how Matthew and Luke start their gospels, but not so with Mark. And unlike John's gospel, Mark doesn't start with the notion of an eternal Logos through which everything was created and which will take on flesh in the person of Jesus Christ. Mark apparently doesn't have time for that. Instead, Mark immediately jumps into the waters of John the Baptist (Mark 1:1-8).

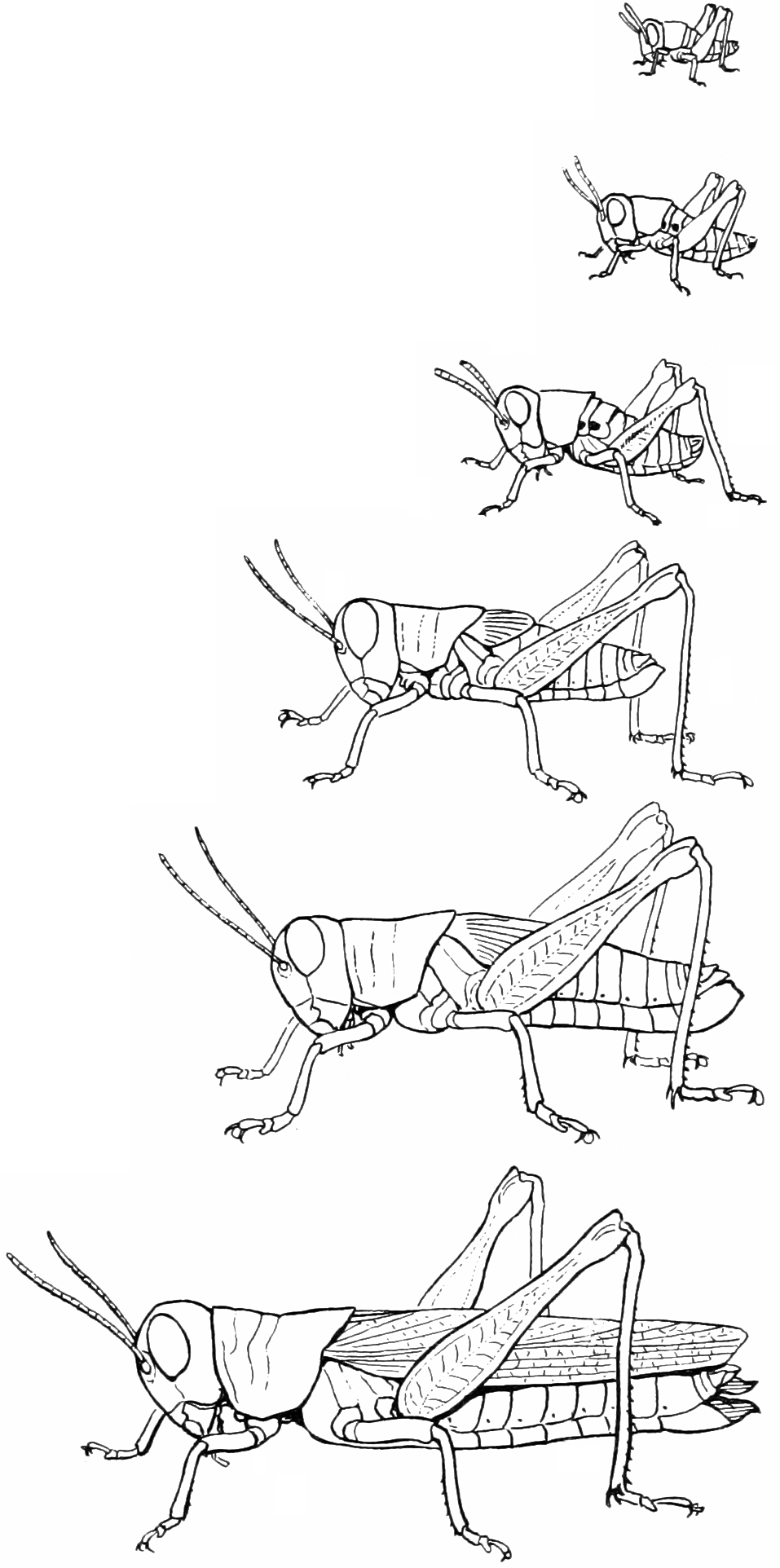

John the Baptist shows up to prepare the way. He's sort of an esoteric character. He lives out in the desert, dresses in scratchy clothing and eats honey glazed grasshoppers. Mark explicitly identifies him with Isaiah's words, but John is also mimicking some of the actions of Elijah here, and some of the things he does or says are echoes of Malachi, Zechariah, Moses and other prophets. At some level, Mark is positioning him as the fulfillment of the whole Israelite prophetic tradition. But if John is preparing the way, what is he preparing the way for?

John was baptizing, he was dunking people into the water. It was a ritual cleansing; it was a metaphor for his message of repentance and forgiveness. Someone greater is coming, and the people needed to get ready. John immerses people in the water as a sign of their repentance; this One who is coming will immerse people in the Holy Spirit.

A lot of people came out to see what this wilderness man, John, was up to. In fact, the Greek text literally says that "the whole countryside of Judea" came out to hear his message and receive his baptism. For Mark, John isn't just preparing, cleansing and preaching repentance to the people, but to the land itself. Perhaps this One comes not only to redeem God's people, but the land too.

One theme often associated with the second week of Advent is Peace. John the Baptist comes and preaches repentance and forgiveness of sins. We repent to God, and pray to God for forgiveness. But we don't only need peace with God - we need peace with other people too. The violence of our sins against our neighbors and our enemies (and, yes, their sins against us) plagues not only ourselves and our relationships, but also the earth itself. In Romans 8 the creation itself painfully groans as it waits for the revealing of the children of God, the children of the God of peace.

We wash our hands before we eat a meal. In a way, baptism serves a similar purpose: we’re also preparing to eat. Revelation and other texts talk about a great wedding feast - a party! - when Jesus returns, but in the meantime when we gather for worship we break bread together. In order to do that we need to wash in the waters of baptism - a sign of repentance and forgiveness - and we need to enact that repentance and forgiveness with our neighbors. Communion or Eucharist or the Lord's Supper is about peace. It's about peace with God, and it's about peace with our neighbors. We wash ourselves of our grudges and make peace for the wrongs we have done, then we feast.

The world is full of germs and dirt and grime and other gross stuff. And, sometimes, so are we. But we have a God interested in making peace with us and with the earth, cleansing us and the earth, and feasting with us upon the earth. In forgiving and in asking for forgiveness, and in baptism and communion, we are preparing the way for the coming of the God of peace.