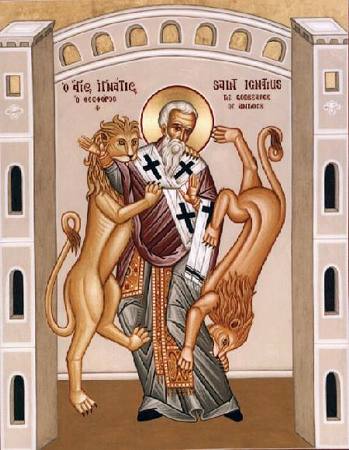

Ignatius of Antioch is a fascinating figure from the early 2nd century. Famous for encouraging Christian unity through obedience to bishops and for getting eaten by lions, he also had a helpful and balanced, if not much elaborated, view on what it means for Christians to read the Hebrew Bible on this side of the Christ event.

In his Letter to the Philadelphians, Ignatius confronts 'Judiazing' Christians, probably not too dissimilar from those Paul confronted, though Ignatius does so with noticeably more gentleness than Paul does in his letter to the Galatians.

Ignatius of Antioch is a fascinating figure from the early 2nd century. Famous for encouraging Christian unity through obedience to bishops and for getting eaten by lions, he also had a helpful and balanced, if not much elaborated, view on what it means for Christians to read the Hebrew Bible on this side of the Christ event.

In his Letter to the Philadelphians, Ignatius confronts 'Judiazing' Christians, probably not too dissimilar from those Paul confronted, though Ignatius does so with noticeably more gentleness than Paul does in his letter to the Galatians.

After offering his trademark prescribed cure for disunity - stand by your bishop - Ignatius proceeds to attack what appears to be the greatest risk to brotherly love within the church in Philadelphia.

He explains that although he is in chains and on his way to his death, he nonetheless has hope because of the gospel message proclaimed by the Apostles. But this message was also proclaimed proleptically by the Hebrew prophets, who themselves "have obtained salvation within the unity of Jesus Christ" and "are included as participants in the universal Gospel hope" (IPhil 5).

But this doesn't mean, for Ignatius, that Christians should practice Judaism. Without Christ we're dead (cue tombstone metaphor), so avoid these kinds of teachings so they don't "weaken your love" (IPhil 6). Instead, cling to the unity of the church.

Ignatius works for unity in the church, because, he tells us, that's the kind of church that God lives in and where forgiveness reigns. So the Philadelphians need to avoid the teaching of factions and instead cling to the teachings of Christ. Ignatius seems to have come across some people when he was in town who told him they couldn't believe any teaching unless it was explicitly written in the "ancient records", the Hebrew Scriptures. They were using the prophets as the measure of the apostolic teaching, and where they didn't find clear precedent for a doctrine in the scriptures they refused to believe it. Ignatius counters:

But for my part, my records are Jesus Christ; for me the sacrosanct records are his cross and death and resurrection, and the faith that comes through him. (IPhil 8)

For Ignatius, that is his justification, that is his proof text, that is his Scripture: the narrative of Jesus, especially his death and resurrection, and the faith - the life of the ecclesia, the church - that springs forth from that Christ event.

Early Christians slowly and organically developed what was called the regula fidei, or rule of faith, which they used as the guideline for interpretation and the development of doctrine. Think of it as an early edition of the Apostles' Creed. But for Ignatius, Christ is the rule of faith. The narrative of Christ is the essential condition of Christian faith and teaching. While Judiazing Christians insist that all belief and practice pass through the litmus test of the Law and the Prophets and the Writings, for Ignatius Christ takes priority as the only litmus test needed. This represents not just a high understanding of the person of Christ, but a profound Christocentrism. The good bishop understood the story of Jesus to be the story through which all other stories are illuminated.